Discover more from Dani | Writes

If you haven’t read the first post in this series, well… I obviously can’t make you do so. But things will make a lot more sense if you do. Here is the link to do that. Go ahead. I’ll wait right here…

My last post finished by concluding that, contrary to the repeated assertions of contemporary critics of complementarianism, I am actually complementarian and I do have the right to describe myself as such.

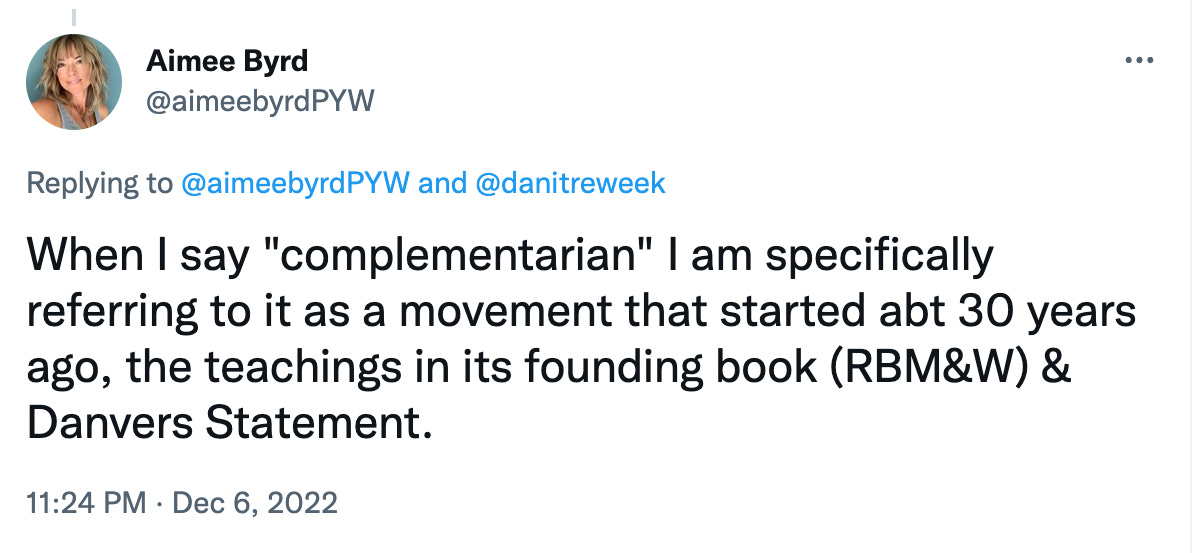

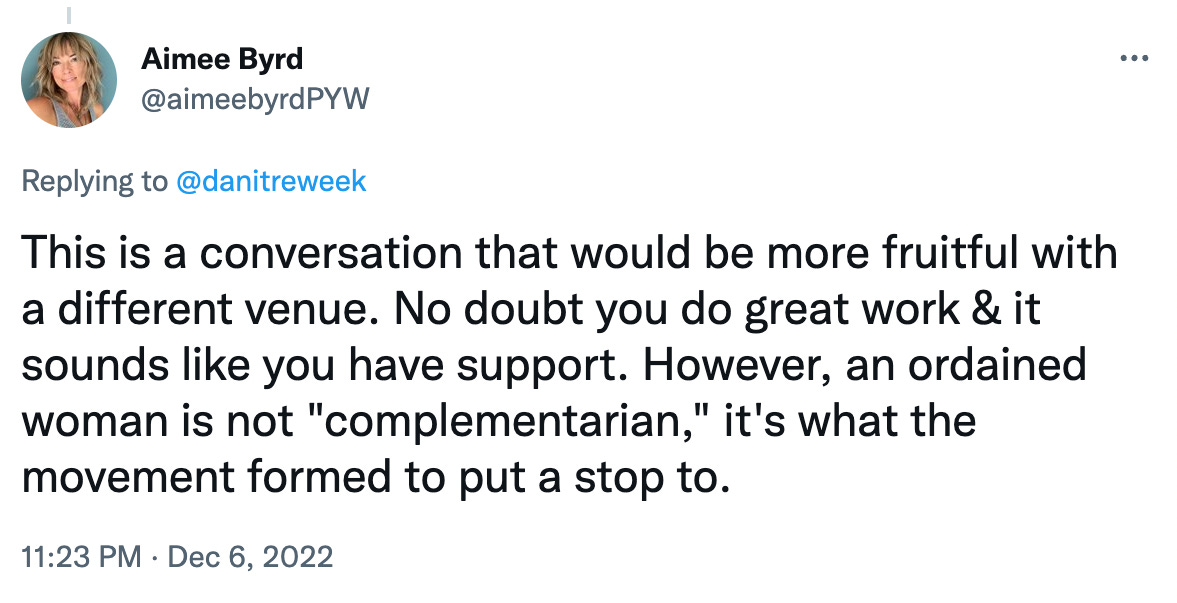

In this post I want to explain the rationale behind that conclusion. But to do so, I need to return to my conversation with Aimee, how she (amongst others) defines the term “complementarian”, and her argument about why the term doesn’t apply to me.

So… What IS in a name?

Here are a few posts from my recent dialogue with Aimee in which she gives insight into her definition of what “complementarianism” is (and isn’t).

Based on these tweets we might summarise Aimee’s definition of “complementarianism” as that which:

Didn’t exist prior to around 30 years ago, that is before the Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (CBMW) essentially invented it.

Finds its ideological definition in the Danvers Statement and the book, Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (RBMW)

Was launched with a defining theological commitment to the eternal subordination of the son (ESS)

Theologically dehumanizes women

Was formed to put a stop to women’s ordination

These are the iconic and necessary features of the “complementarian movement” as Aimee has defined it. And she’s not alone in that definition. As I observed in my last post, contemporary (mainly US ex-complementarian) critics of complementarianism have a very specifically constructed definition of exactly what they have determined is to be called complementarian. And so also a very specifically constructed definition of who is allowed to call themselves complementarian.

But how accurate is that definition? Well, to answer that question, we’re going to work through each of the features summarised above.

1. Was complementarianism invented 30 years old by CBMW?

Well, yes. But also no. As tends to be the case with all manner of things, it’s more complicated than that. This requires a little bit of detailed work, so hang in there with me, OK?

One of the founders of CBMW, Wayne Grudem, wrote that he and his co-founders coined the term “complementarianism” in 1988 as ‘a one-word representation of [their] viewpoint’.1 From the available evidence, it does seem that they did indeed coin that term as a shorthand way of referring to the particular theological framework they had developed (more on that later).

However, the root word “complement” had already been used by various other commentators as they spoke about the relationship and roles of men and women. For example, egalitarian author Kevin Giles, argues that “Egalitarian evangelicals had long before this date embraced this term as the best way to designate the male-female relationship”.2 As such, Giles is somewhat outraged that those who held the conservative counter-view to his made the word their own. However, the difference is that even as egalitarian authors spoke about men and women being "complementary", they didn't coin or utilise the term "complementarianism" to refer to their distinct and integrated theological framework of such complementarity. That might seem like a pedantic point, but it isn't. The 1988 coining of the term "complementarianism" referred to a theologically detailed and integrated understanding of what a particular group of people believed it actually meant (theologically and pastorally) that men and women complement each other.

The outraged wind in Giles’ sails dies down even further when you consider that some non-egalitarian commentators had also already been using the root term “complement” as a reference to a more conservative/traditional understanding of male/female relationships. And this was well before the actual -ism was coined in 1988. For example (and I’m indebted to the work of Jane Tooher, my friend and the co-author of Embracing Complementarianism, for this insight), back in 1980 Stephen B. Clark (a Charismatic Roman Catholic author) wrote the following in his book, Man and Woman in Christ—

In some ways, the term "complementarity" best sums up the relationship between the man and the woman in Genesis. "Complementarity" implies an equality, a correspondence between man and woman. It also implies a difference. Woman complements man in a way that makes her a helper to him. Her role is not identical to his. Their complementarity allows them to be a partnership in which each needs the other, because each provides something different from what the other provides. The partnership of man and woman is based upon a community of nature and an interdependence due to a complementarity of role.3

[…]

Again, the primary question at issue is how male leadership and female leadership are to be structured together. Complementarity between men and women is of great value, but it need not be expressed within the same position or role.4

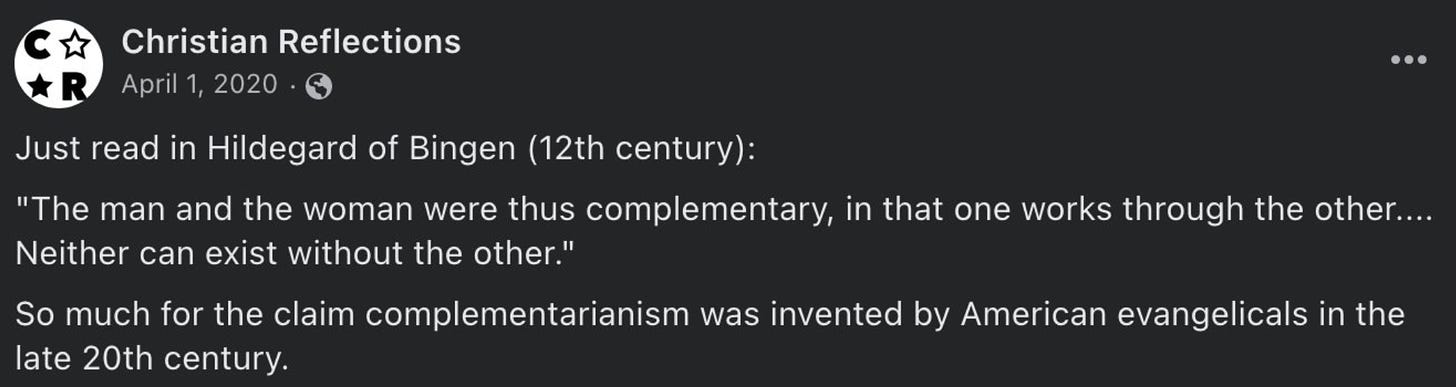

But of course, Clark wasn’t the first to emphasise the complementarity between men and women in their relationships with each other and the way they expressed those relationships in the world. For example, the Centre for Biblical Equality themselves admit that, “Calvin emphasised the complementary relationship between men and women”. Or take this medieval example that an acquaintance recently alerted me to:

But here’s the thing folks. Coining a term is different to inventing the foundational ideology that lies behind that term.

The term complementarianism itself—that is, the -ism—does appear to have been coined by a group of American evangelicals in the late 20th century (1988 to be precise) as a shorthand representation of the particular theological framework they were asserting. However, they didn’t just invent that theological framework from scratch. Indeed, we have seen that Christians throughout history spoke about men and women being complementary to each other. The term “complementarianism” was coined to refer to one particular way that one particular group thought that complementarity was to be faithfully understood from Scripture and expressed in relationship.

While the term “complementarianism” was new, what it sought to reflect was not itself new. Indeed the founders of the term wanted “to help Christians recover a noble vision of manhood and womanhood as God created them to be.”5

Complementarianism is thus only 30 years old in the sense that it is a 30 year old movement seeking to recover something much older and more original - a biblical vision of genuine complementarity between men and women.

Having said all of that (at some length, sorry!), I actually think the relative age of “complementarianism” is far less relevant to the definition of what (or who) is and isn’t in its name than the next question on our list…

2. Is complementarianism defined by the Danvers Statement and the book, Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (RBMW)?

Firstly, some facts.

The Danvers Statement was written by “several evangelical leaders at a CBMW meeting in Danvers, Massachusetts, in December of 1987. It was first published in final form by the CBMW in Wheaton, Illinois in November of 1988”. It has a threefold structure of 1) rationale, 2) purposes and 3) theological affirmations of a “Biblical vision of sexual complementarity”. In other words, the theological framework that the -ism refers to is explicated in The Danvers Statement.

Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (RBMW) is a book which was published in 1991, three years after Danvers and which contains 26 different chapters (essays) and two appendices, all of which seek to exegetically, theologically and pastorally engage with the doctrinal commitments that were outlined in Danvers. That is to say, RBMW is not the founding theological document of complementarianism. That is Danvers.

One of the purposes of Danvers was to “promote the publication of scholarly and popular materials representing this view”. RBMW is the most extensive earliest example of just that. In it a range of scholars and theologians sought to consider how complementarianism (as it is theologically framed by Danvers) might be understood and applied. This means that RBMW was not a large and monolithic set of doctrinal statements that defined complementarianism. Indeed, in the original 1991 preface, the editors’ themselves wrote:

Twenty-two authors from many denominational backgrounds contributed to this book, and it is inevitable that not every author would agree with every detail in the chapters written by the other authors or by the editors.

RBMW made a significant contribution to the formation of the complementarian movement as it grew in various places in the 1990s and beyond. However, plenty of complementarians (then and now, including myself) don’t agree with plenty of stuff in RBMW. Put another way, no particular claim in RBMW (that wasn’t already and explicitly affirmed in Danvers) can be said to be definitive of the complementarian movement.

So no, the various statements, arguments and conclusions found in RBMW are not definitive of what complementarianism is. If you are complementarian then you’ve probably been theologically informed by some of the material in RBMW. But if you are complementarian (in the -ism sense of that word), then you are theologically committed to the doctrinal positions outlined in Danvers.

Let me furnish you an example by turning to our next question.

3. Was complementarianism launched with a defining theological commitment to the eternal subordination of the son (ESS)?

No.

The Danvers Statement makes no assertion of, reference to or allusion about Jesus being eternally subordinated to the Father. Let me state it again, the doctrinal statement which clearly set out the theological framework of complementarianism does not “launch” with a defining theological commitment to ESS.

Yes, one of the original founders of complementarianism (Wayne Grudem) holds to ESS. He (somewhat briefly) speaks to that in Appendix 1 of RBMW. He and some other prominent complementarian scholars have written about it elsewhere (although they also differ with each other at various points and some have even shifted their own position). But let me remind you of what the editors—one of whom was Grudem himself!—said in the original 1991 preface of RBMW:

…not every author would agree with every detail in the chapters written by the other authors or by the editors.6

Sarah Allen summarises it perfectly in her excellent article on a British perspective on the contemporary complementarian discussion (which you most definitely should read in full, especially if you have little understanding of complementarian expression outside of a US context)

Though this conception of the doctrine of God had repeatedly been part of the articulation of complementarianism by several key figures, notably Bruce Ware and Wayne Grudem, it was not logically essential to the presentation of complementarianism in RBMW. Nevertheless, ESS became almost a symbol of all that was perceived to be wrong with CBMW…

CBMW president, Denny Burk agrees:

I am a Danvers complementarian. That view of gender is not and never has been reliant upon an analogy to the Trinity. Biblical complementarianism neither stands nor falls on speculative parallels with Trinity. It may be that some writers have pushed such analogies, but that has never been an essential ingredient of Danvers complementarianism.

Some, maybe many, complementarians (and egalitarians!) would very much like to see CBMW (as a key complementarian organisation and the foundational organisation behind Danvers) develop a more publicly formal doctrinal position on ESS. However, the point remains that the -ism was not launched with a defining theological commitment to ESS. Holding to theological complementarity does not require one to hold to ESS. It never has.

4. Is complementarianism a theology that dehumanizes women?

No.

I’ll keep this brief because this really is a complete furphy (if you don’t know what that Aussie-ism means, click here). Here are some extracts from the Danvers Statement:

Both Adam and Eve were created in God’s image, equal before God as persons and distinct in their manhood and womanhood (Gen 1:26-27, 2:18).

The Old Testament, as well as the New Testament, manifests the equally high value and dignity which God attached to the roles of both men and women (Gen 1:26-27, 2:18; Gal 3:28).

With half the world’s population outside the reach of indigenous evangelism […] no man or woman who feels a passion from God to make His grace known in word and deed need ever live without a fulfilling ministry for the glory of Christ and the good of this fallen world (1 Cor 12:7-21).

… to help both men and women realize their full ministry potential through a true understanding and practice of their God-given roles…

Again and again, Danvers is at pains to emphasise the full dignity, value and humanity of women.

But, for the sake of the argument, what about RBMW? Well, from the 1991 preface written by Piper and Grudem:

“We hope that thousands of Christian women who read this book will come away feeling affirmed and encouraged to participate more actively in many ministries, and to contribute their wisdom and insight to the family and the church. We hope they feel fully equal [emphasis original] to men in status before God, and in importance to the family and the church […] Similarly, we desire that every Christian man who reads this book will come away feeling in his heart that women are indeed fully equal [emphasis original] to men in personhood, in importance, and in status before God, and, moreover, that he can eagerly endorse countless women’s ministries and can freely encourage the contribution of wisdom and insight from women in the home and church…”7

Was complementarianism a movement which grounded itself in a dehumanizing theology of women? No. No it was not.

5. Was complementarianism formed to put a stop to the ordination of women.

No.

The Danvers Statement makes no reference to ordination whatsoever. The closest it gets is saying that “some governing and teaching roles within the church are restricted to men (Gal 3:28; 1 Cor 11:2-16; 1 Tim 2:11-15).” While that has implications for ordination it is simply not the same as saying that there is not ever any legitimate place for any women to be ordained to any office within the church. In my case, my (complementarian) denominational context celebrates the ordination of women as deacons.

But again, for the sake of the argument let’s look at what RBMW has to say on the subject (even though I’ve already evidenced that RBMW is not definitive of complementarianism itself) . As far as I can tell, there is only one discussion about ordination in RBMW and the posture of that chapter is not anti-women’s ordination. Indeed, the author concludes:

Insofar as the New Testament is concerned, ordination is not a major issue, if it exists as such at all. Most churches and denominations have developed ordination beyond New Testament precedent in both its form and its significance. […] The question for evangelical Christians who feel bound by its testimony of Holy Scripture then becomes not, “Who can be ordained"?” but, more simply, “Who is qualified to serve in ecclesiastical officers?”.8

So, no. Complementarianism was not formed to “put a stop” to women’s ordination.

Will the real Complementarianism please stand up?

Right then. Answering those questions means we are left with two additional questions:

If those definitive features of complementarianism aren’t actually definitive features of complementarianism then:

How did we get to the point where people are consistently saying they are?

Where do we go from this point on?

1. How did we get here?

Well we got here because like any movement, complementarianism has been taken up by many people in idiosyncratically dynamic ways. I’ll speak more about this in the third and final post in this mini-series. But for the moment I simply want to observe that Aimee (and others’) specific, narrow and self-selectively identified definition of complementarianism fails to take that into account. She and others have been terribly hurt, disappointed and harmed by the actions of some (many?) in their contexts, who claim to be complementarian and to have acted in the interests of their complementarianism. I deeply lament and grieve that. Truly, truly, I do. I wish they had never had to endure that.

One of the results of that hurt, disappointment and harm is that Aimee and others have confused the part with the whole. They have determined that the things they (often very rightly) object to in the way complementarianism has been expressed in their context is characteristic and in fact definitive of complementarianism itself. They have determined that the way those particularly complementarians have behaved towards them is characteristic and in fact definitive of the way all complementarians behave always.

But as we have just seen above, that is simply not the case. History is being rewritten and wars are being waged against a Frankenstein-ed enemy.

That needs to stop—not the least for the sake of women. It’s time that we recommit to complementarian history as it actually stood and start aiming our (metaphoricl) punches specifically at those who really do dehumanize, diminish and denigrate the daughters of Eve.

2. Where do we go from this point on?

I’ll spend a little more time thinking about where to from here in a broader sense in my next post. But let me finish by making some comments with respect to the focus of this post and the previous one—namely my critique of how Aimee (and others) define and then seek to dismantle complementarianism (and those who claim to hold to it).

Aimee’s definition of complementarianism (as representative of the wider contemporary definition being critiqued) doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

Complementarianism is a contemporary theological (and so also pastoral) movement which reaffirms biblical principles revealed in Scripture about the ontological and relational realities of manhood and womanhood in God’s design. These principles are explicated in the theological affirmations laid out in the Danvers Statement that was published in 1988.

What this means is:

If someone wants to claim that another person is not complementarian

If they want to generalise about complementarianism itself being rotten to the core

If they want to dismiss all complementarians as being misogynists who can’t listen and who don’t promote women into any forms of leadership

… then it is incumbent upon them to evidence and demonstrate these things …

not in relation to one particular claim or another by one particular author or another in one particular chapter or another of RBMW or some other resource they has since been published

not in relation to how specific contemporary organisations, denominations or individuals have taken it upon themselves to idiosyncratically develop complementarianism into particular expression and practice (many of which I am ever eager to admit have been disappointing, harmful, detrimental and even abusive)

…but instead, in relation to the doctrinal commitments of The Danvers Statement.

If you want to critique complementarianism as an entire movement, then you need to theologically critique Danvers. Indeed, if you want to dismantle any particular expression or instance of that which claims to be complementarian but is producing horrid fruit, then the absolute best way to do that is by holding them accountable to their own terms of reference: i.e., Danvers. I’ll be right there alongside you, cheering you on.

If you want to critique complementarianism as an entire movement, then you need to be aware of the diverse landscape of how the theological commitments of Danvers have been diversely and dynamically applied throughout the evangelical world. That doesn’t mean you need to know everything in detail, but it does mean you need to know that there is an everything. It means you need to stop throwing darts at the part, while doggedly mistaking it for the whole.

If you want to assert that someone who claims to be complementarian actually isn’t, , then you need to make that assertion on the basis of how their theological convictions align (or misalign) with the theological convictions which define the -ism itself, and/or on how the application of those theological convictions is being unfaithfully expressed in practice.

To make it personal, if you want to argue that I—a woman who is ordained, a theological scholar and a Christian leader—am either mistaken, misguided or lying when I say I am complementarian, then evidence that argument with reference to ME. Evidence it with reference to what I believe. With reference to what I do. And with reference to how any and all of that does or does not align with the foundational theological principles of the complementarianism I claim to believe and uphold as found in The Danvers Statement.

In the third and final post in this mini-series we’ll spend a bit more time thinking through how we might understand, make sense of and carefully navigate the complex complementarian landscape of the contemporary moment in a way that is genuinely honest, faithful, constructive and loving.

Wayne Grudem, “Personal Reflections on the History of CBMW and the State of the Gender Debate,” The Journal for Biblical Manhood & Womanhood 14, no. 1 (2009): 14.

Kevin Giles, “The Genesis of Confusion: How “Complementarians” Have Corrupted Communication,” The Priscilla Papers, 29, no. 1 (2015), 27.

Stephen B. Clark, Man and Woman in Christ: An Examination of the Roles of Men and Women in Light of Scripture and the Social Sciences. (The University of Michigan: Servant Books, 1980), 23.

Stephen B. Clark, Man and Woman in Christ: An Examination of the Roles of Men and Women in Light of Scripture and the Social Sciences. Servant Books (The University of Michigan: Servant Books, 1980), 629

Piper, John, and Wayne Grudem, eds. Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism. (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2006), xv.

Piper, John, and Wayne Grudem, eds. Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism. (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2006), xv.

Piper, John, and Wayne Grudem, eds. Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism. (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2006), xv.

Piper, John, and Wayne Grudem, eds. Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism. (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2006), 251.

Subscribe to Dani | Writes

Just a female theologian thinking deeper about (some) things that matter. Mainly singleness, marriage, sex and most importantly Jesus. All writing here is free. Always.

Hi Dani - I’m thinking through related issues, and I’m wondering whether complementarian theology has a view on women writing theological text books/commentaries. Do you see authoring an academic text as holding teaching authority over the audience that reads it? And I mean a text aimed at theological teaching and research, not an apologetic or historical or narrative style publication. I’m not sure yet how to view that one or what I think about the issue. I’d value your view on that. Thanks.